At the Church-Waddel-Brumby House Museum, we believe it is vitally important to educate the public on both the positive and negative aspects of our antebellum house’s history. On this webpage, we welcome you to read A History of Black Athenians at the House and Enslaved Persons in the World of Dr. Moses Waddel, in order to learn more about the history of slavery tied to the House and its various owners.

A History of Black Athenians at the House

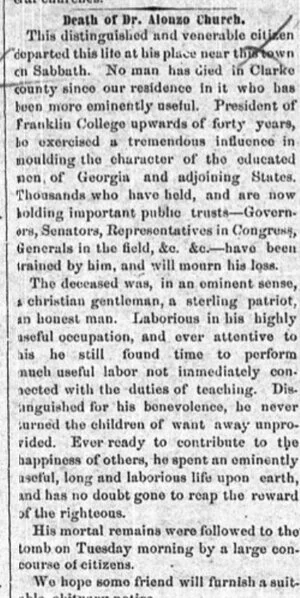

Alonzo Church

Alonzo Church was born in April 1793 in Brattleboro, Vermont. Alonzo Church worked as an educator in his home state of Vermont before relocating to Putnam County, Georgia, and later coming to Athens to teach at the College. He succeeded Moses Waddel after his resignation as the sixth president of the University of Georgia, a position he held for 30 years.

During his tenure at UGA and until his death in May 1862, Church enslaved a number of people, including 6 persons whom he left to his children.

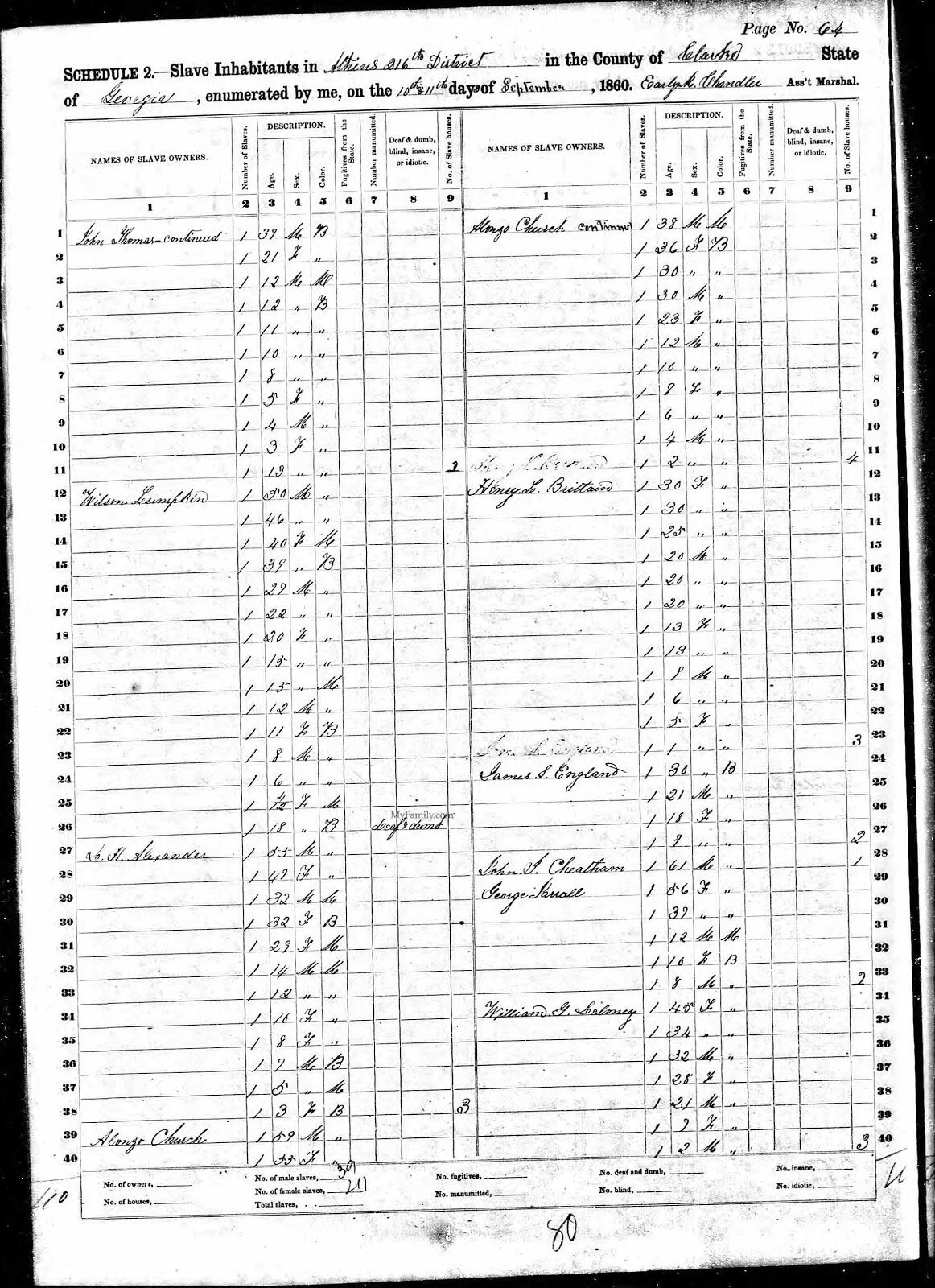

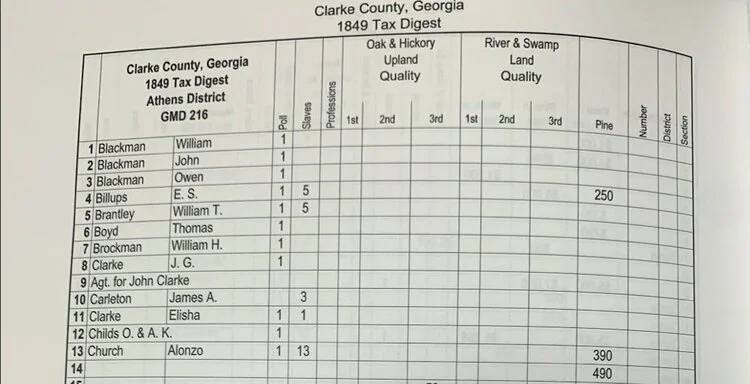

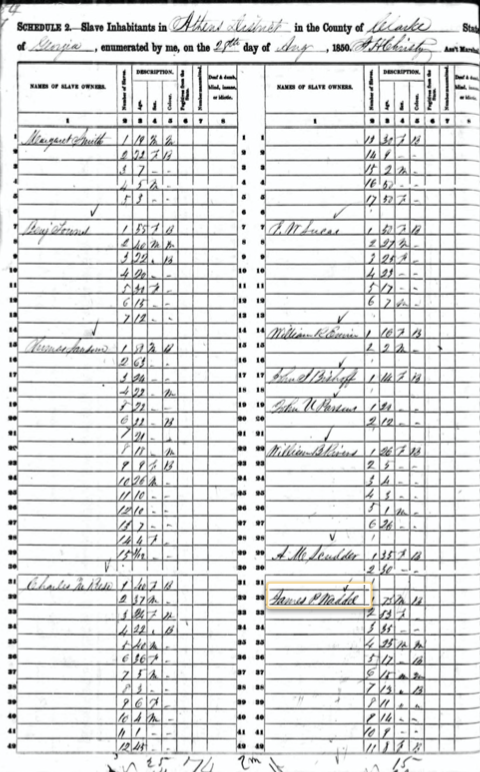

Georgia censuses and probate records have provided lots of insight into the history and finances of enslavers in Athens during the post-reconstruction era. The 1849 Clarke County tax digest is one of the first listings of the enslaved persons of Alonzo Church; he is listed as having 13 enslaved persons in his household. In 1850, the Clarke County slave census records 9 people enslaved by the Church family.

These censuses often list the number of persons enslaved by each Athens resident as well as the gender and age of each enslaved person, but rarely record their names. There is also mention of enslaved persons on an 1861 probate record of Alonzo Church.

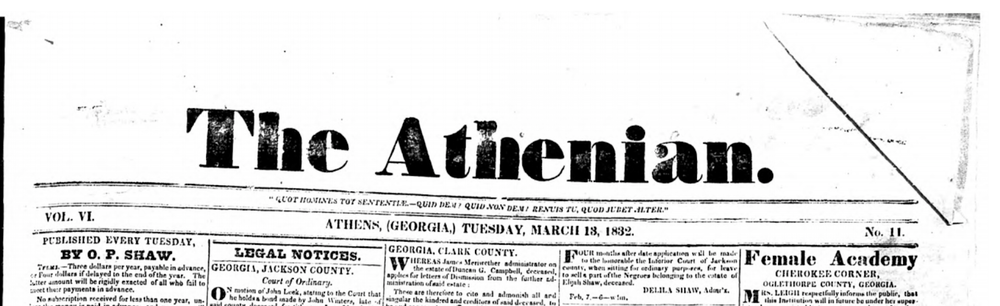

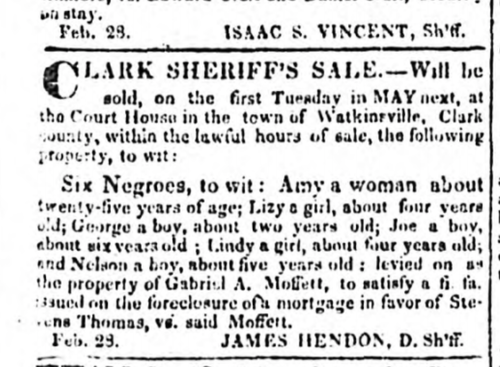

In addition to being recorded in official Athens-Clarke County government documents, enslaved persons were often listed for sale in Athens newspapers such as The Athenian and the Southern Banner. Children as young as a year old were sold away from their families weekly in these papers.

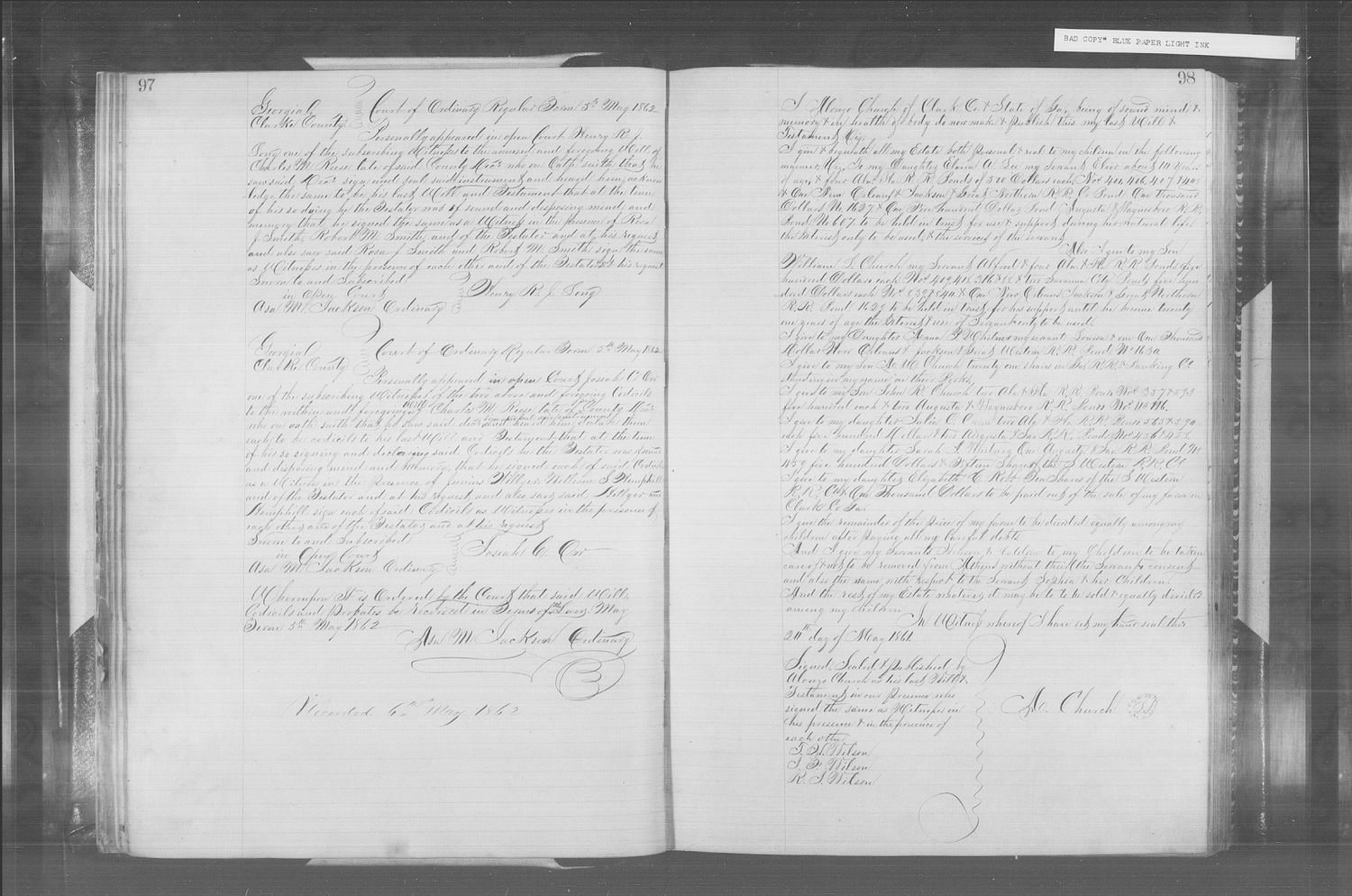

The last will and testament of Alonzo Church shows record of 6 individuals (of the 9 he enslaved) at the time of his passing; their names were Alfred, Caloline, Elvir, Hanson, Lousia, and Sophia. The 3 individuals unaccounted for in these records are likely Sophia’s children. However, there is no official record of their names.

His will, written March 23, 1863, read as follows:

“To my daughter Elvina A, I give my servant Elvir about 10 years of age… Also I give to my son, William L. Church, my servant Alfred... I give to my daughter Anna P. Whitmer, my servant Louisa. I give the remainder of the price of my farm to be divided equally among my children after paying all my lawful debts. And I give my servants Hanson and Caloline to my children...and also the same with respect to the servant Sophia and her children.”

Athens Clarke County Slave Census, 1860Athens Clarke County Tax Digest, 1849Will and Probate Records, Alonzo Church, 1861Church is mentioned in several local papers like The Athenian.News clipping announcing the sale of enslaved children.Church’s obituary was printed in the Southern Watchman. Moses Waddel

Moses Waddel, born in Yadkin, Rowan County, North Carolina in June 1770, was a minister and Christian theologian. Waddel established the Willington Academy in Willington, South Carolina, in 1804. He taught and ministered in South Carolina for many years before accepting the position of president of the University of Georgia, a position he held from 1819 to 1829.

The 1820 U.S. Census lists 16 enslaved people belonging to Moses Waddel, including 9 children under the age of 14. A few years prior to his father's death, James P. Waddel was given primary ownership of the Waddel family slaves, and under the 1847 tax digest, 12 people were listed as slaves of the James Waddel family. There are eleven people reported as James Waddel’s slaves according to the 1850 Census.

Dr. Moses Waddel founded Willington Academy in 1804 for a sect of elite Georgians and South Carolinians, along with the Willington Presbyterian Church. Here, he ministered and taught before coming to Athens, Georgia. Prior to the Willington Academy, he founded the Log Cabin School. In 1985, Dr. James Lewis MacLeod, a descendant of Willington graduates, wrote, The Great Dr. Waddel: Pronounced Waddle, a full length novel on the life of Moses Waddel based on his experience and study of theological seminary. What he writes can be corroborated by Moses Waddel’s diary, written from 1821 until he suffered a stroke in September of 1836.

Dr. MacLeod’s writings on plantation life with the Waddel’s revealed much about the character of the Waddel family. Moses Waddel initially enslaved 23 people on a 400 acre farm in Willington, South Carolina prior to relocating to Georgia, most of whom he bought as a dowry for his second wife Elizabeth ‘Eliza’ Pleasants.

Waddel refused to accept a salary for preaching and had to resort to working on his farm alongside enslaved people in addition to preaching to make up for lost income. In the winter, enslaved women would pick and dry fruit while men repaired farm fences and cleared land. As can be seen in his September 21, 1830 diary entry, Moses Waddel would often go out on the farm and watch slaves pick cotton and pick cotton alongside them; he even promised to buy them hats if they increased their workload.

However, Moses Waddel’s treatment of those he enslaved can be considered puzzling at best. Waddel’s son John believed his treatment of slaves was too kind; John wrote that his father was the “most humane master...no cruel treatment was ever known or permitted, and every reasonable liberty was allowed them” and that his father’s kindness would “ruin all the Negroes in the neighborhood.” However, Moses Waddel’s own diaries show Waddel worked his slaves ruthlessly, particularly in the winter and forced them to learn long biblical texts and Christian theology for his own pleasure. He chaired a Presbyterian committee for the religious education of slaves in 1833 and required that all his slaves be religiously educated. Waddel also did not hesitate to beat slaves for idleness, laziness, or cursing.

But according to his September 20, 1824 diary entry, a few students at the University of Georgia once called Waddel to prevent a slave on campus from being abused by a faculty member. And, in a January 26, 1831 diary entry, Waddel described the sight of “a drove of Negroes--14 chained” as “most unpleasant.”

From these diary entries, it seems Moses Waddel had no qualms with mistreating his slaves when he deemed necessary, but hated the sight of other enslaved people being mistreated.

Athens Clarke County Slave Census, 1850Captain John W. Brumby

Captain John W. Brumby was the patriarch of the Brumby family. He acquired the Church-Waddel-Brumby House by marriage to Arabella Hardeman, the granddaughter of Sarah H. Harris, who purchased the house from Dr. Waddel circa 1833. Born in January 1843, he was a member of the Confederate States Army and had four children including two sons, Wallis and Frank, and two daughters, Anne and Mary. Frank served as a four-star admiral in the U.S. Navy, and Anne served as the second dean of women at the University of Georgia. Anne and Mary later inherited the house.

The least is known about Captain Brumby and his relationship with enslaved persons. However, there is evidence to suggest that he hired two enslaved carpenters named Alexander and Elijah from his father, Arnoldus Vanderhorst Brumby of Marietta, in 1864. Hypothetically, Captain Brumby may have been able to hire these men from his father for less than he would have paid another enslaver. Upon their hire, they would have been sent to Athens for the time allotted on a “slave payroll.”

Slave payrolls documented the loan of enslaved persons to other enslavers over a specific period of time. These payrolls often included the name of the enslaved person, the intended occupation, and the amount paid for their hire. It should be noted that all pay went to their enslavers.

Research continues to be done to learn more about Captain Brumby’s relationship with Black Athenians and slavery, as well as that of Dr. Church and Dr. Waddel.

However, in 1936, the Federal Writers’ Project conducted a series of interviews with former slaves, many of whom resided in Athens. These “Slave Narratives” offer the most accurate depiction of life for enslaved people in Athens though very few of them can be linked to the Church, Waddel, or Brumby families.

Given the nature of slavery and family separation, it is difficult to confirm and trace the family history, but the interviewee here, Alice Bradley is believed to be the daughter of Caloline, a woman enslaved by Alonzo Church. However, in the interview Alice has a difficult time recalling a portion of her family history.

Narratives like this one, from formerly enslaved Athens native Willis Cofer, depict the most accurate picture of slavery Athens. Family separation and community and identity dissolution caused by chattle slavery makes it difficult to locate the descendants of slaves in Athens and piece together the complex history of enslaved peoples.

1864 Slave Payroll, National Archives War Department Collection of Confederate RecordsNarrative by Alice Bradley, from the Federal Writers’ ProjecNarrative by Willis Cofer, from the Federal Writers’ ProjectSydney Phillips is an intern at Historic Athens and student at the University of Georgia studying political science and public relations with a minor in Portuguese. Connect with her on LinkedIn or download a presentation of her research for the Historic Athens Welcome Center.

Enslaved Persons in the World of Dr. Moses Waddel:

1821 to 1831

Dedicated to writing in his journal daily, with the exception of instances where he was incredibly ill, Dr. Moses Waddel, D.D., Presbyterian minister and fifth president of the University of Georgia, chronicled his day-to-day life and the people involved in it– including those who he enslaved or hired from other enslavers. Between 1821 and 1831, the names of 40 enslaved Black Georgians and South Carolinians can be found noted in his entries: Old Dick, Solomon, Dick, Edmund, Ned, Old Ben, Young Ben, Lewis, Cyrus, Mary, Sophy, Vilette, Leanna, Kizzy, Creecy, Cicero, Gracy, Julia, Richard, Roxanna, Juley, Harry, Dicy, Andrew, Nelly, Harvey, Manuel, Sukey, Henson, Midas, Fanny, Wat, Jacob, Tully, Abraham, Stepney, Fredrick, Rupert, Joe, Hannah, and Matilda. The following descriptions of their responsibilities and experiences are entirely compiled from context clues found throughout the aforementioned journals.

Due its subject matter, this narrative contains content that may be troubling for readers.

-

The earliest appearance of a name belonging to an enslaved person is that of a man named Dick Newton, on July 1, 1821. Despite its shortness, this entry provides an important piece of information about him: that he was able to write[1]. Dick’s name appears a total of twenty-five more times over the following ten years. Though he was heavily involved in Dr. Waddel’s life, it was not until 1829-30 that Dr. Waddel purchased Dick from Ebenezer Newton. Prior to that, it can be surmised that Dr. Waddel hired Dick on all other occasions to assist him in his day-to-day life by cleaning his room, running errands, acting as a driver and a courier, and ringing the College bell, as well as working as a field hand on his plantation. Dick married an enslaved woman in October of 1830 whose name was not noted by Dr. Waddel at the time he mentioned the marriage[2]. Presumably, this woman could have been Juley, whose name appears along with Dick in a June 12, 1833 letter to John Waddel, Dr. Waddel’s youngest son. By this time, Dr. Waddel was living in Willington, South Carolina, and his Athens plantation was being managed by his son-in-law, Edmund Atkinson, the husband of his eldest daughter, Sarah. The letter states that Mr. Atkinson was “resolved on selling Dick Newton and Juley” because they were both “such thieves” that he could not “endure to keep them or be troubled with them.” In the aforementioned letter, Dr. Waddel explained the reason behind this accusation, telling his son that Dick and “two or three other” enslaved persons, per Mr. Atkinson, had broken into houses on the plantation, stolen corn and sold it to the stores in town.

-

There are a few instances in Dr. Waddel’s journal, between 1822 and 1827, where an enslaved man named Old Dick is mentioned. Based on context, Dick and Old Dick were two different men - Dick being enslaved at the time by Ebenezer Newton, and Old Dick being enslaved by Stevens Thomas[3] before presumably having been purchased by Judge Augustin Clayton[4]. While Dr. Waddel lived in Athens, Old Dick is one of three enslaved people, along with Gracy and Cicero, who he mentions buying things for at Christmastime. On Christmas Eve of 1824, it was noted that he “bought clothes and shoes for Old Dick.”

-

Solomon first appears on August 29, 1822, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “came for corn.” While he occasionally ran errands for Dr. Waddel and acted as a courier and a driver, Solomon seems to have most commonly worked as a field hand at the Waddel plantation—cleaning oats, plowing the corn-lot, manuring the garden, hauling fodder, cutting brush, and trimming trees. It was not unheard of for Dr. Waddel to work alongside the people whom he enslaved, and one example of this occurred on March 18, 1830, when he and Solomon planted seventeen peach trees “in the yard.” Based on context, these peach trees would have been planted in the yard of his home in Willington, South Carolina, where his family had settled once again only a month or so before Mrs. Eliza Waddel passed away after a prolonged illness.

On the subject of illness, on February 10, 1827, Dr. Waddel noted that Solomon was sick and had nailed a horseshoe to his threshold. Aside from the horseshoe being a symbol of good luck, some superstitious minds believed that magical, healing properties of the iron within the horseshoe would ward off demons who brought disease[5]. Solomon’s name continues to appear in journal entries written after Dr. Waddel moved his family back to Willington, South Carolina, which suggests that he moved along with them.

-

Edmund first appears on July 25, 1822, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “came with oats.” Based on context, Edmund primarily worked as a field hand at the Waddel plantation. He put up fences, hauled sand, packed cotton bales, and plowed the fields and gardens. During his time in Athens, Dr. Waddel had his in-town home on present-day Hancock Avenue and his out-of-town plantation. He occasionally mentions passing Peter Puryear’s on his way to and from the plantation, which suggests it would have been located in between Athens and Watkinsville, perhaps in present-day Oconee County, which did not form until 1875. The Puryear brothers, Peter and John, appear along with Edmund in two of Dr. Waddel’s journal entries. On November 26, 1824, Dr. Waddel noted that he heard of John Puryear whipping Edmund, which “disturbed” him. The following day, he talked with Peter Puryear about his brother’s aggression toward Edmund. Later on, it appears that Edmund, along with Solomon, moved to South Carolina when the Waddels relocated just before Mrs. Waddel’s death in 1830. Dr. Waddel noted on February 9, 1831, that he saw Edmund cutting brush wood in a swamp with Mr. Wells, the Overseer of his Willington plantation.

-

Ned first appears on September 1, 1822, when Dr. Waddel noted “Ned here wrong.” There was no explanation of what he meant. It appears that he most commonly worked as a field hand, and occasionally acted as a courier. In one instance, he and another man enslaved by Dr. Waddel, named Ben, were hired by William Sutherland to hive bees. Ned is another who moved with the Waddel family to South Carolina, and he seems to have been one of two more objectively rebellious men enslaved by Dr. Waddel, the other being Lewis, during his time living in both Athens and Willington. More often than not, his name appears in the context of his excessive drinking, for which he was rebuked by Dr. Waddel in one instance[6].

-

Lewis first appears on November 25, 1822, when Dr. Waddel noted Major Newton coming over after night to “bargain about Lewis.” Most entries where his name appears were written either just before or after the Waddels moved back to Willington. However, entries predating the family’s relocation suggest that Lewis was primarily at the house in town[7]. On December 16, 1829, Lewis returned to Athens after having run away to Alabama. He spent nearly the entire month of January in the gaol, or jail, in Watkinsville. On February 25, 1830, for an unspecified reason, Lewis was “taken away.” Nine days later, Dr. Waddel received a letter from a Mr. Hodges about him. Once the family relocated to Willington, Lewis seemed to work once again at their home rather than their plantation—doing such things as grubbing and cleaning the yard.

On April 26, 1830, Dr. Waddel was “roused in [the] night by Mr. Wells about Lewis.” The following day, “men called with Lewis tied.” There is no mention of what led to these events. It is possible that Mr. Wells, as Overseer of the plantation, found Lewis missing while checking to ensure everyone was accounted for. In a panic, he roused Dr. Waddel from his sleep to inform him before setting out with a group of men in search of Lewis. When they found him, possibly the following morning, they bound him and took him to Dr. Waddel for his instruction on what to do next. This can only be surmised, as this subject was never touched on again.

-

Old Ben, sometimes referred to as Ben, first appears on December 24, 1822, when Dr. Waddel noted that “Old Ben came.” Old Ben worked as a courier, a gardener, and a field hand, and ran errands for Dr. Waddel, often picking up his mail. He built fences, hauled bricks, washed wheat and took it to be milled. As was mentioned earlier, it was not unheard of for Dr. Waddel to work alongside the people whom he enslaved. Other examples of this were provided when he mentioned working with Old Ben to fence in a field of walnut trees, and picking cotton in Willington with both Old Ben and an enslaved woman named Creecy. When he was not working, Old Ben would preach to other men and women enslaved by Dr. Waddel[8].

-

On March 17, 1830, a Young Ben appears for the first time when Dr. Waddel noted that he “spoke much with Young Ben.” In an instance where Dr. Waddel spent a day getting his umbrella mended, his sulkey shafts lengthened, and visiting his friends, he was accompanied by Young Ben. Later in the evening, John N., possibly his son John N. Waddel, joined them and played the flute for Young Ben by moonlight[9]. On October 8, 1830, Young Ben started toward Athens with Dr. Waddel and his youngest daughter, Mary Anna. On the way, his shoes were stolen. They reached Athens at two o’clock the following afternoon, and spent two days there before heading back toward South Carolina, stopping for rest in Lexington, Georgia, on the way. Young Ben drove Dr. Waddel’s carriage thirty-six miles the following day to the town of Petersburg, Georgia, the remnants of which would be flooded one hundred and twenty years later to create Clarks Hill Lake. They spent Wednesday, October 13, in Willington before starting toward Fairview, South Carolina, where they spent five days at a religious camp-meeting.

-

Cyrus first appears on November 17, 1824, when Dr. Waddel noted that “Old Ben and Cyrus started home.” On March 27, 1827, Dr. Waddel “scolded Cyrus about boots.” His reason is not specified, but one could surmise that Cyrus either lost or heavily damaged his boots and needed to be provided with a new pair because, a few days later, Dr. Waddel did just that[10]. Cyrus worked primarily as a field hand, often being noted as plowing or preparing corn fields at Dr. Waddel’s plantations in Athens and Willington. In one instance, while Dr. Waddel was picking cotton with Old Ben, Creecy, and other unidentified enslaved persons, he “made Cyrus pick” as well. While traveling around Georgia in early April of 1827–from Athens to Macon, and through Sparta and Warrenton on the way to Augusta—Dr. Waddel was accompanied by Cyrus. On this journey, while they were in Warrenton, Georgia, Cyrus “misbehaved” and Dr. Waddel “corrected him.” It is not specified what Dr. Waddel considered misbehavior in this instance.

-

Creecy appears for the first time on August 30, 1823, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “saw no working but Dick carrying fodder and Crecy washing.” Her name does not appear again until after the Waddel family had relocated to Willington, South Carolina, and she was noted as being sick in two of the few entries in which her name appears. The other entries suggest that, during the time she was enslaved on Dr. Waddel’s plantation, she seemed to work as a field hand, doing things such as picking cotton and hauling wood. On August 17, 1830, an enslaved woman named Dicy appears in an instance where Dr. Waddel “visited [his] farm and saw Creecy sick and Dicy.” Her name appears only two more times, both in January of 1831, when Dr. Waddel noted seeing her spinning on her repaired spinning wheel and that a Mr. A. whipped her for “laziness.”

-

Cicero first appears on December 25, 1824, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “bought clothes for Gracy and a blanket for Cicero.” His name appears four more times, all in March of 1830, primarily in context that suggests he was preparing fields for planting at the Waddel plantation which may have been leased to a Mr. McClinton. In one instance, Cicero and Old Ben hauled bricks for the chimneys of a house that was being built. Gracy, mentioned earlier, only appears in one other entry besides the one that first mentions Cicero. On December 13, 1830, Dr. Waddel was given three blankets and he gave two to Gracy and an enslaved woman named Roxanna. This is the only entry in which Roxanna’s name is mentioned.

-

Juley appears for the first time on December 22, 1830, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “started Juley and the children at noon,” referring to sending his children homeward. There is mention of an enslaved woman named Julia on January 9, 1825, but it is unclear whether she and Juley were one in the same. When Juley appears in December of 1830, it seems that Dr. Waddel had hired her from a W. Mills. On February 22, 1831, Dr. Waddel noted that he “called [and paid] W. Mills for Juley [and] Company.” Juley left Willington, South Carolina, the following month and began working on Dr. Waddel’s plantation in Athens, which was then managed by his son-in-law, Edmund Atkinson[11]. Juley appears once more in an aforementioned letter to John Waddel, Dr. Waddel’s youngest son, on June 12, 1833, where he states that Mr. Atkinson was “resolved on selling Dick Newton and Juley” because they were both “such thieves” that he could not “endure to keep them or be troubled with them.” Atkinson did not wish to sell either Juley or Dick without Dr. Waddel’s consent, but he made clear that his wife, Sarah, Dr. Waddel’s eldest daughter, was “quite willing to let them both go.”

-

Nelly appears for the first time on March 8, 1830, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “visited Nelly and Vileth sick.” Nelly had a son named Andrew, and, on September 11, 1830, she “[brought] and showed her sick child with rising on [his] head and neck.” Three days later, Dr. Waddel noted that he visited the quarters and that Andrew was ill. He “visited L. Andrew”, presumably Little Andrew, a week later and twice more over the following three days. On September 24, 1830, he noted that Andrew had gotten better. Andrew’s mother, Nelly, may have been either married to or partnered with an enslaved man named Harry. Their names appear together in one entry, where Dr. Waddel noted that he gave them money. This is the first instance where Harry’s name appears and it only comes up in four other entries between September of 1831 and March of 1831, in which he is said to have hauled items, split wood, and delivered a load of planks for a house that was being built. Vileth, or Vilette, whose name appears alongside the earliest mention of Nelly, only comes up three times. Besides the aforementioned entry, her appearances are far apart: on March 15, 1824, when E. Calahan “came for her,” and on May 20, 1830, when Dr. Waddel saw her and two boys thinning crops at his farm.

-

Leanna and Kizzy both appear for the first time on January 29, 1824, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “whipped Leanna and Kizzy.” His reason for doing so was not mentioned, and this is the only time that Leanna’s name appears. Kizzy comes up three more times, many years later in March, April and July of 1830, when Dr. Waddel noted that he irritated her about her child’s name, that she was sick, and that Henry King came late one day and asked for her.

-

Abraham and Wat both first appear on November 3, 1829, when Dr. Waddel noted “Abrm. and Wat picked cotton in [unknown].” The original document had been damaged, resulting in sections of missing text, so it is difficult to say whether Dr. Waddel noted the location they were in or the time of day during which they picked the cotton. The few other entries in which Abraham and Wat appear suggest that they worked as field hands, doing things such as preparing corn rows, cutting logs and splitting wood for fence rails. An enslaved man named Tully cut logs and split wood along with Abraham and his name appears in three other entries, one of which states that Dr. Waddel whipped him for “urinating before [him].”

-

Midas first appears on March 12, 1830, when Dr. Waddel noted that he “bought [a] cap for Midas at Walker’s.” His name appears in three other entries between March and June of 1830 and their context suggests that he worked as a field hand and as a driver, and was occasionally hired by other enslavers[12]. On June 15, 1830, Midas and an enslaved woman named Fanny took two of Dr. Waddel’s children, Isaac and Mary Anna, from Willington to Athens. This is one of only two times Fanny’s name appears. In the first instance, Dr. Waddel simply noted that she was sick.

-

Sukey and Mary both appear for the first time on March 23, 1824, when Dr. Waddel noted that “Sukey whipped Mary severely.” This is the only instance in which Mary’s name appears. Prior to more of Dr. Waddel’s journals being discovered, it was assumed based on context that Sukey may have been a name or nickname of the Overseer of Dr. Waddel’s Athens plantation. However, it became evident later that Sukey was an enslaved woman, when her name appears in one more entry from January 13, 1831, which states that she brought three blankets to Dr. Waddel and he gave her two of them[13].

The remaining twelve names primarily appear in single entries, many without great context. Jacob and Frederick appear together on October 11, 1828, when Dr. Waddel noted that there was “much fuss” on that day by a “negro trial” for Jacob and Frederick. An enslaved woman named Hannah appears twice: once with Old Ben, when Dr. Waddel sent Dick for a paddy wagon to carry them from Athens to Willington, and again when Dr. Waddel noted that he got castor oil for her. Harvey burst a bale of cotton on November 12, 1830, Dr. Waddel scolded Richard for “idleness” on February 1, 1826, and Sophy gave birth on January 27, 1823. Stepney traveled to and from South Carolina with Old Ben and Ned, bringing back three bushels of flour and a large melon, on September 6, 1828. Dr. Waddel saw Rupert cutting wood to fuel a fire on February 4, 1829, and saw Henson lying on a wagon when he visited his plantation on July 14, 1828. On June 15, 1830, Dr. Waddel sent an enslaved woman to his son James whom he referred to as “negress Matilda.” Based on context, Joe and Manuel were enslaved by Major Bull and Colonel Ware, respectively. Dr. Waddel noted on March 4, 1829, that he saw Joe threshing, and in August of the following year he noted that he “heard by Isaac King of [the] death of Mrs. Bull’s Joe by ox cart.” On July 9, 1823, Dr. Waddel was roused by Manuel who requested that he visit Colonel Ware.

Based on census records alone, it would not be possible to pair names with the responsibilities and experiences of these Black Georgians and South Carolinians enslaved by Dr. Waddel and other white southern planters in the early nineteenth century. As stewards of the Church-Waddel-Brumby House, we are fortunate to have not only a detailed account of Dr. Waddel’s day-to-day life, but also a record of the names of these people who played a crucial role in his life’s functionality and the maintenance of his homes and plantations through the distasteful binds of slavery.

1. “Dick wrote.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1821.

2. “Spoke of Dick’s marriage to ye others.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1830.

3. “Called at Mr. Thomas’ store – p’d him $45 for old Dick’s hire.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1823.

4. “Spoke to Judge C. in his garden about old Dick’s hire.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1827.

5. The Folk-lore of the Horseshoe, Journal of American Folklore, 1896.

6. “Ned drunk – rebuked him late.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1824.

7. “Lewis made no fire till 11 ½.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1824.

8. “Heard old Ben preach in kitchen.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1828.

9. “John N. went with me. He played on the flute for young Ben p.m. by moonlight.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1830.

10. “Got Cyrus shoes at Welch’s.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1827.

11. “Rec’d a letter from Mr. Atkinson about Juley’s arrival.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1831.

12. “Maj’r Bull called wt. Midas.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1830.

13. “Sukey bro’t 3 blankets, gave her two.” Diary of Dr. Moses Waddel, 1831.

Caitlin Short is a long-time staff member of Historic Athens, an advocate for inclusivity, preservation of historic resources and telling the full story, and a dedicated steward of the Church-Waddel-Brumby House.