Indigenizing Athens Self-Guided Walking Tour

This tour begins on S Lumpkin Street, just North of Carlton Street, and goes through campus, local parks, and downtown. The distance between these sites can be quite far, so it may be best to do a combination of driving and walking.

Created for Historic Athens by Margo Sullivan, with support from the Gable Foundation

Jump to Tour Stops

History of Indigenous Settlement in the Athens Area

Indigenous settlement in Georgia can be traced back at least ten thousand years ago. Traditionally, tribal people situated their communities on fertile lands along rivers, creeks, barrier islands, and other flowing bodies of water. With the power to cultivate and forage off the land and water, native communities expanded into advanced civilizations, with organized governments, division of labor, advanced technologies, religion, craftsmanship, and hierarchical social structures.

Early settlements in Georgia were concentrated on the coast. People living in these coastal communities caught fish, harvested shellfish, and constructed shell mounds throughout the region, some reaching nine feet in height. As time went on, their civilizations expanded and people began to move across Georgia taking their cultural practices with them.

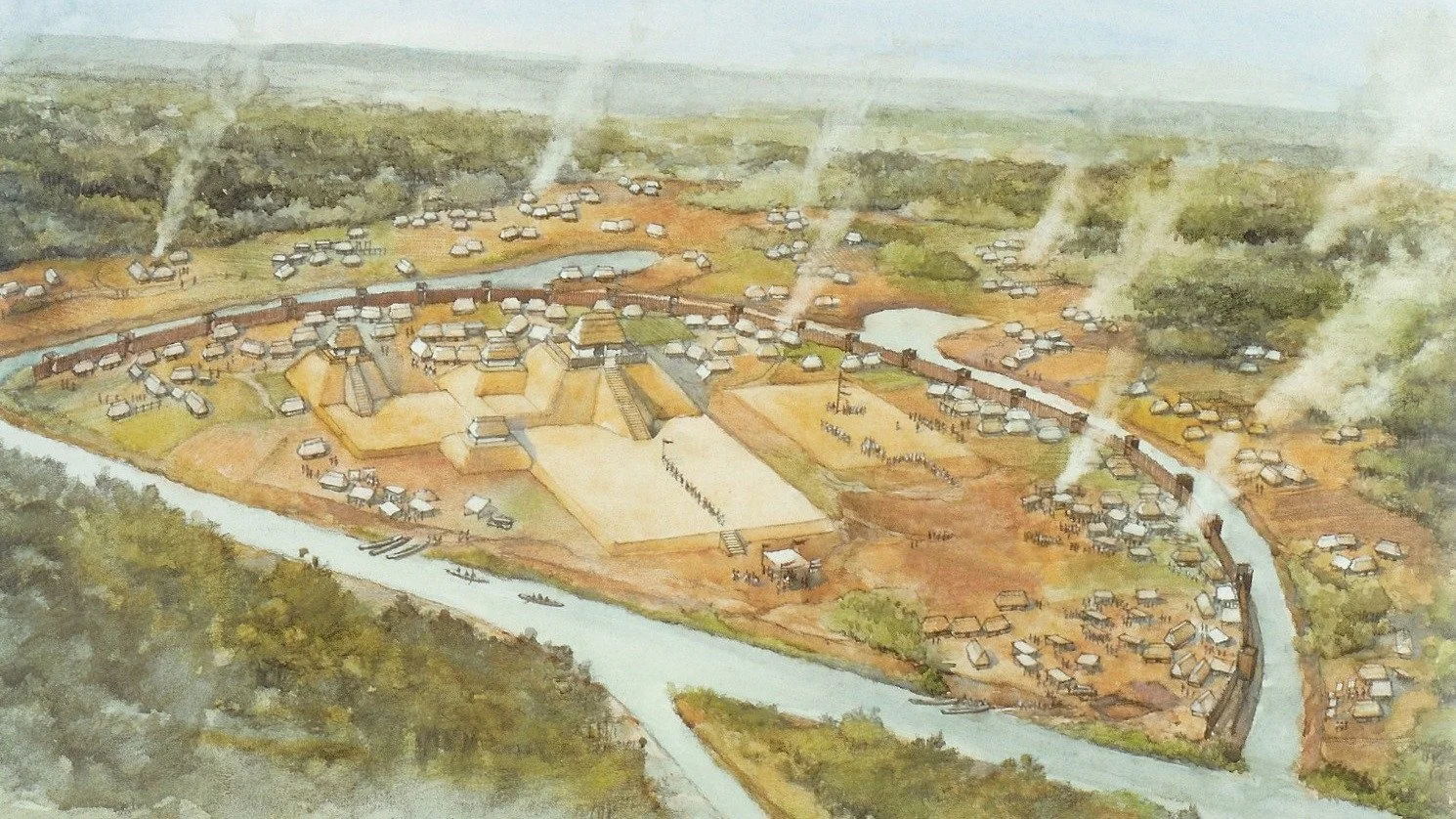

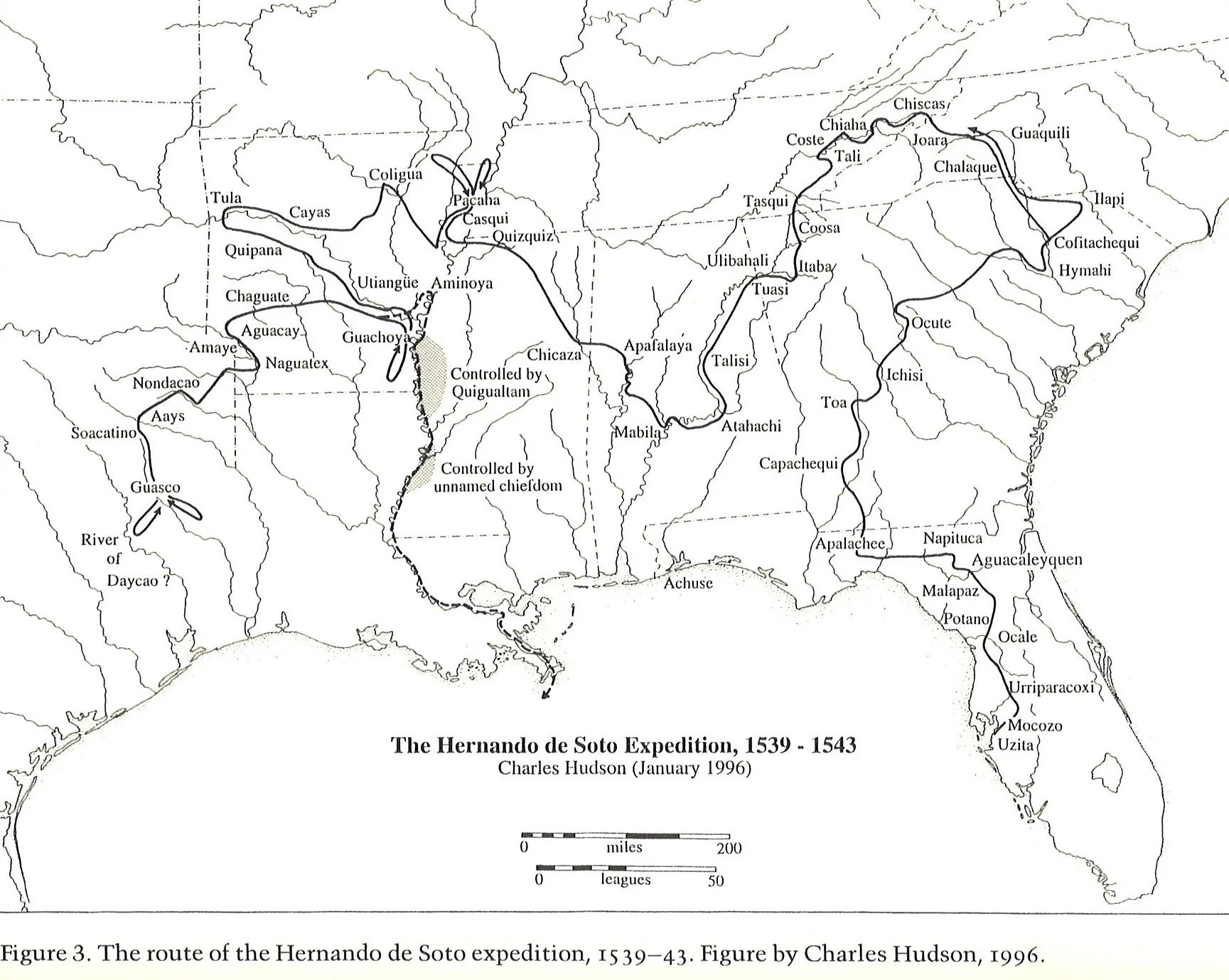

During the Mississippian era (930-1700 C.E.), Muscogee people created large ceremonial complexes and constructed earthen mounds. These mounds were multi-functional, serving as platforms for homes and temples or as funerary complexes. In the archaeological record, mound center civilizations flourished for hundreds of years. However, these civilizations underwent a transformation in the 1540s when Spanish soldiers led by Hernando De Soto landed in present-day Tampa and moved North into Georgia. Following waterways, DeSoto and his men traveled through Georgia and encountered various Muscogee-speaking tribal nations along the way. As a result of this cultural cross-over, indigenous communities were exposed to violence and new diseases, leading to a period of social strife that altered their traditional living arrangements.

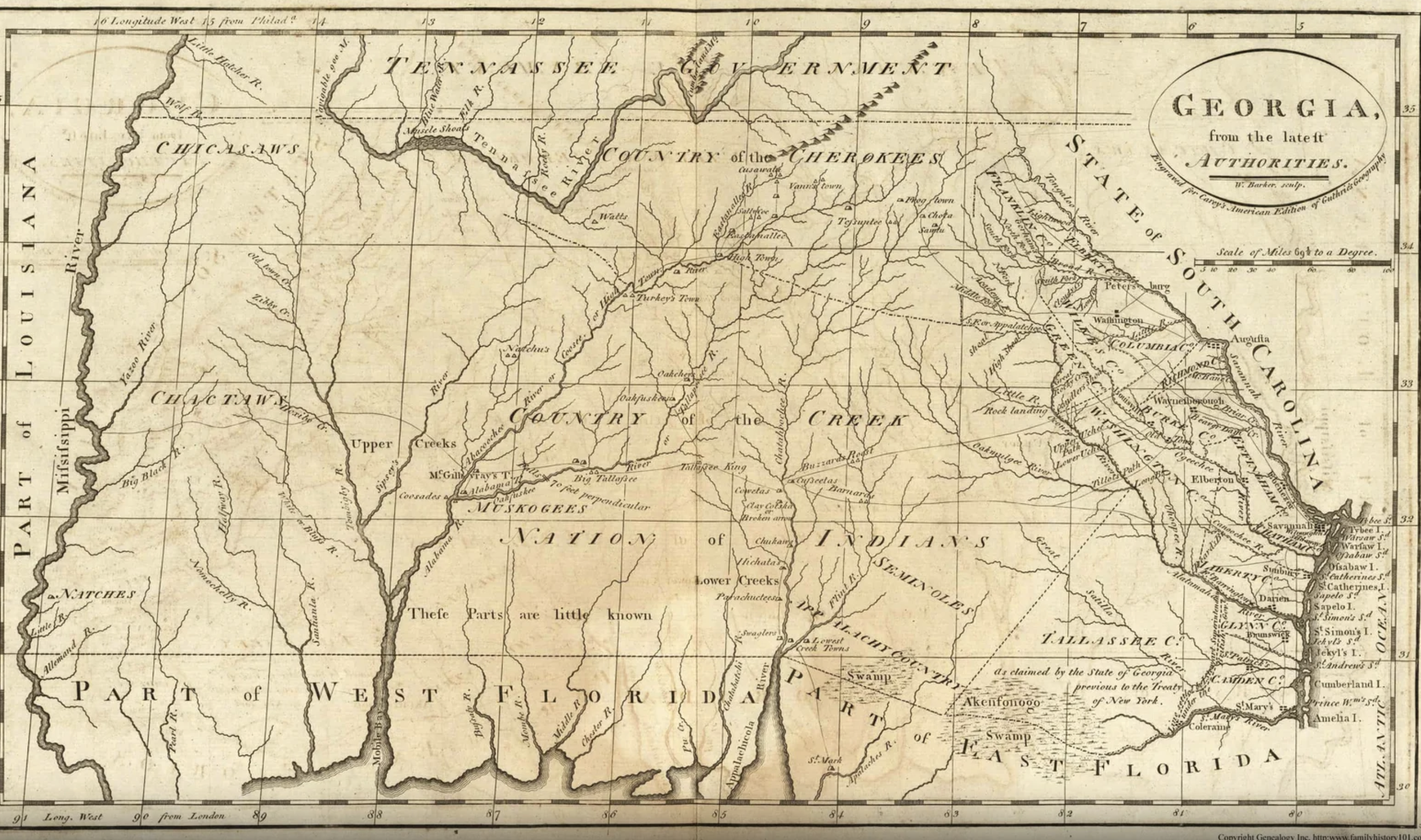

Despite the transformation of these Oconee River communities, tribal people were able to preserve their culture, language, religion, and history and continue their way of life today. As they adapted to the negative impacts of settler colonialism, they continued their way of life and established homesteads, dispersed throughout the area. It was at this time that the Oconee Plateau region, the floodplains along the Oconee River, became the most popular habitation site in Georgia, acting as home to Muskogean tribes. Interestingly, the word “Oconee” means “skunk” in Hitchiti, a dialect of the Muskogean language.

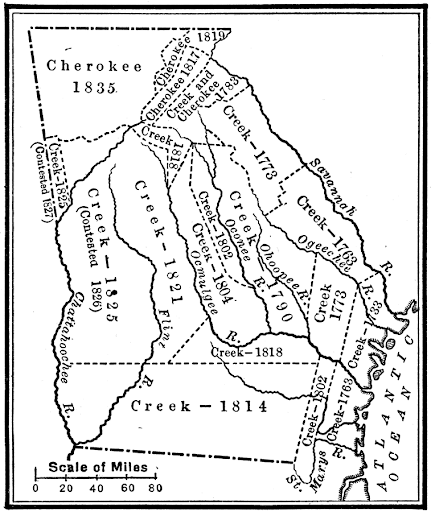

From the 1600s to the 1830s, indigenous tribes continued inhabiting their ancestral lands throughout Georgia, with Cherokee civilizations concentrated in the northern half of the state. However, as colonial settlements spread from the Savannah River to the Oconee River in the 1700s, tribal people lost much of their sovereign land and were forcefully pushed west. With the establishment of the University of Georgia and the town of Athens, Muscogee and Cherokee people were displaced from their ancestral lands, with prominent Athenians playing a part in their systematic removal.

Representation of a Mound Center from Etowah, just about an hour from Athens, Georgia

Old map of Muscogee territory

De Soto’s expedition through Georgia exiting east of the Oconee River valley was mapped by former UGA anthropologist Charles Hudson based on historical accounts and archaeological evidence. De Soto initially passed through the town of Capachequi in Southwest Georgia and continued northeast taking him through Toa on the Flint River, the major mound center of Ichisi, thought to be the present-day Ocmulgee mounds, Altamaha, (Milledgeville), Ocuutay, (Sparta), and Coofahquei (Greensboro), roughly 35 miles south of Athens.

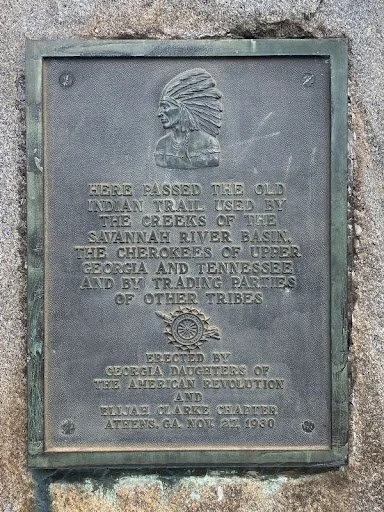

Daughters of the American Revolution Marker

On S Lumpkin St, Athens, GA, 30605

North of Carlton, across the street from 1088 S Lumpkin St, on the side of the South Lumpkin Street Parking Deck

33*56.73’ N, 83*22.712 W

Nearby parking: South Lumpkin Street Parking Deck - behind the marker

This marker was placed on S Lumpkin Street in 1930, erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution. The plaque features a silhouette of a person in a feather headdress with an inscription below. The inscription reads “Here passed the old Indian trail used by the Creeks of the Savannah River Basin, the Cherokees of Upper Georgia and Tennessee, and by trading parties of other tribes.” While this marker acknowledges indigenous presence in the area, it does not address the full truth. The land the city of Athens and the University of Georgia rests on was originally indigenous land, home to the Muscogee and Cherokee nations. However, this marker makes no reference to indigenous possession of this land. The inscription recognizes a far-off indigenous presence while also negating their land rights. Additionally, the inclusion of the feather headdress on the marker perpetuates an inaccurate, stereotyped image of native people. Despite what some may think, feather headdresses are not included in the ceremonial regalia of all Native American tribes. For example, neither the Muscogee nor the Cherokee traditionally wear feather headdresses of this sort.

Marker Inscription

Marker

Lumpkin House

145 Cedar Street, Athens, GA

Nearby parking: South Campus Deck

Instructions: As a UGA office building, it is requested that people do not enter the building.

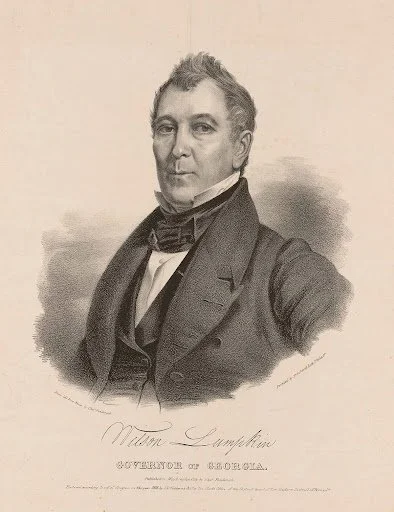

This Greek Revival-style home was the residence of Wilson Lumpkin, a notable political figure in Georgia’s antebellum past. Situated on the highest point of his land, Lumpkin lived in this home from its completion in 1844 to his death in 1870. Born in 1784, Lumpkin began his political career in the 1810s and throughout his career held local and state government positions, was elected to Congress four times, and served as Governor of Georgia for two terms (1831-35). After his governorship, Lumpkin then served as U. S. commissioner to the Cherokee people. In addition to his political roles, Lumpkin was also a Trustee of the University of Georgia. After his death, the land of Lumpkin’s estate was gradually sold to the University of Georgia by Lumpkin’s daughter, Martha Atlanta Lumpkin Compton. In 1907, she sold the remaining acreage and the house to the University, under the condition, “that the house be kept intact or the property would revert to her heirs.” Today, the home sits in its original location and currently acts as the office building for the Department for Agricultural Business.

Local knowledge suggests that Lumpkin’s occupations as “Commissioner to Cherokee Indians” and slave owner impacted the building of the structure, from its site and material to its architectural plan. Firstly, to provide him with a good viewpoint to see any incoming invaders, the structure was built on the highest spot on his land. Secondly, the structure was made of stone and featured thick exterior walls to act as fortifications for the home. Additionally, it is believed the house was built on top of an above-ground basement, which remained empty, to add an extra layer of protection from any invaders.

In local lore, it is believed that Lumpkin was worried scorned tribal people would burn down his home in retaliation for his involvement in Indian Removal. However, all natives in Georgia had been systematically removed by the mid-1840s, so it is more likely that Lumpkin heard of the Nat Turner Rebellion of 1831 and as a slave owner, built his home in anticipation of a slave rebellion on his own land.

Wilson Lumpkin

Portrait of Martha Atlanta Lumpkin Compton in the entrance hall

Interior room of Lumpkin House

Stairwell of Lumpkin House

Exterior of Lumpkin House

Lumpkin Grave/Monument, Oconee Hill Cemetery

Grave: West Hill Lot 181 Oconee Hill Cemetery, Athens, GA,

Directions: As you enter the cemetery, veer right to go up West Hill and walk around the paved path, eventually there will be a set of small stairs that lead to the center of the burial plot.

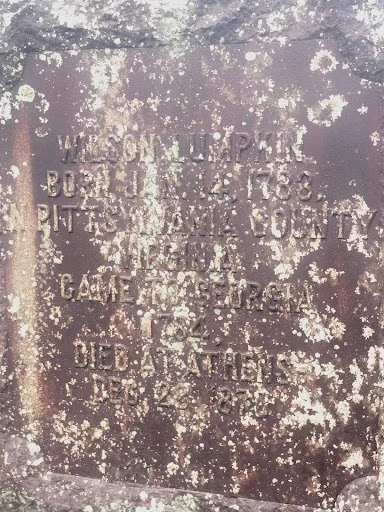

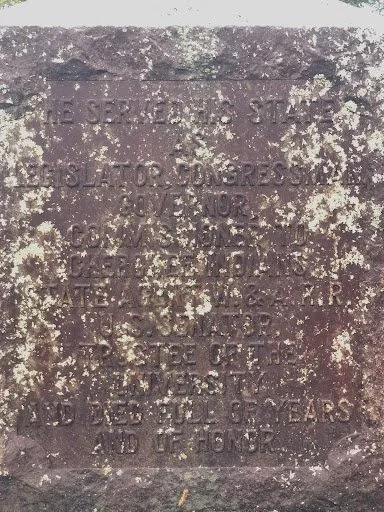

Similar to the positioning of his home, Lumpkin chose his burial spot at the highest point in the cemetery. His gravesite consists of two structures, an obelisk, and a funerary monument. Interestingly, the obelisk was built during Lumpkin’s lifetime. According to local legend, he would have been able to see it from his home which faces northward towards Oconee Hill Cemetery. Beside the obelisk is Lumpkin’s funerary monument which was erected posthumously and consists of a series of stacked stone slabs. On top of the third slab, sits a large stone cube with a pyramidal top that features two funerary inscriptions. The front of the monument has an inscription that follows the format of a standard grave and features his name, date of birth and death, and some biographical information.

Front Inscription:

“Wilson Lumpkin

Born Jan 14, 1788,

In Pittsylvania county

Virginia

Came to Georgia

1784,

Died at Athens

Dec 28, 1870”Back Inscription:

“He served his state

as legislator, congressman,

governor,

commissioner to

Cherokee Indians,

state agent W. & A. R. R.

U.S. Senator,

Trustee of the

University

and died full of years and of honor”While Lumpkin held many positions during his political career, his particular mission in public life was Cherokee Removal. As “commissioner to Cherokee Indians” Lumpkin was backed by the Jackson Administration which asserted “that control over the Cherokees in Georgia was the exclusive responsibility of the state.” In his many political positions, he worked diligently to organize and oversee Cherokee removal, with his final contribution to the cause being his effort in the Senate “to block John Ross's efforts to turn the treaty or postpone the removal deadline.”

-

“I believe the earth was formed especially for the cultivation of the ground, and none but civilized men will cultivate the earth to any great extent, or advantage. Therefore, I do not believe a savage race of heathens, found in the occupancy of a large and fertile domain of country, have any exclusive right to the same, from merely having seen it in the chase, or having viewed it from the mountaintop.”

Lumpkin, Wilson, 1783-1870. 2008. The Removal of the Cherokee Indians from Georgia. Martino Pub. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=edshtl&AN=edshtl.102676835&site=eds-live

Diagonal view of Lumpkin gravesite

View of Lumpkin gravesite with obelisk

Front inscription of Grave

Back inscription of Grave

Cedar Shoals

Around 592 Oconee St, Athens, GA 30602

Nearby parking: North Oconee Greenway Park on Oconee Street. Coming from Williams St. turn right onto Oconee St. Take an immediate right into the North Oconee Greenway parking lot. From here, follow the trail till you come to a wooden lookout point, here you can see the shoals.

This location, called Cedar Shoals, has been a prominent place in Athens’ history, used by both natives and colonists alike. The shoals, considered a great food source, were also commonly used for recreation and navigation. The shoals and its banks provided food sources such as fish, mussels, blueberries, blackberries, pecans, and more. To efficiently collect large amounts of fish from the river, tribal people engineered fish weirs using hand-woven nets made of twine and rivercane to direct fish to a targeted area. Typically, Muscogee and the Cherokee people identified rocky areas of rivers as ideal locations to efficiently create weirs. When necessary, the natural placement of the rocks could be altered to achieve a funnel shape, desirable for guiding fish into the weir. Weirs made of wood and acted as a dam, trapping the fish. In these live traps, the fish could be harvested easily. In addition to its vital role as a food source, Cedar Shoals was deemed an ideal spot for crossing the Oconee River and for enjoying nature. The site would have hosted recreational activities, and community gatherings, and would have also been used by people to relax.

-

While natives used the shoals for food, travel, and recreation, colonists forcefully established their own place along the river. In 1785, the University of Georgia was chartered, funded by a 40,000-acre grant of Muscogee land, unjustly given by the Georgia General Assembly. Despite this charter, the location of the university wasn’t selected until 1801. That summer Abraham Baldwin and other notable figures including John Millegde selected land close to a spring off of the North Oconee River to act as the site for the country’s first public university. To actualize this plan, John Milledge purchased 633 acres from Daniel Easley, millowner and inn runner, and donated it to UGA. At this time, Abraham Baldwin began leading “negotiations” with the Muscogee and Cherokee people. However, these negotiations featured an unequal power dynamic, and tribal people approached the issue at a disadvantage. Baldwin’s efforts, backed by the support of the federal government, resulted in the Compact of 1802 in which the United States government promised to extinguish native land titles in Georgia, effectively creating the first organized forced removal in Georgia. With the fate of their lands decided for them, Muscogee and Cherokee families were forcefully removed from their ancestral homeland.

North Oconee River Greenway sign to look for near parking lot

Land Theft in Georgia

Cedar Shoals, view of possible fish weir

View past the rocks, where people may cross river

View of rushing water leading up to rocky area of shoals

Dudley Park

100 Dudley Park Rd, Athens, GA, 30601

Nearby Parking: Dudley Park, Firefly Trail, & North Oconee Greenway Parking Lot, on E Broad Street, between Mulberry St. and First St.

Located in North Athens, Dudley Park is a 31-acre park set along Trail Creek and the North Oconee River. Although the park was established in 1953, the territory was in use long before that. At Dudley Park, one can still find remnants of an indigenous past in the form of bedrock mortars. In the Archaic era (6000 B.C. - 750 A.D.), native people used rocks along rivers to grind beans, nuts, and other plant seeds into pastes and food. To crush the seeds, natives used a tool equal to a modern-day pestle to push the seeds into the rock. As a result of this repetitive pressure, circular indentations in the rocks formed. These indentations are called bedrock mortars. As seen here, the mortars can be different sizes and have different depths depending on the force used to grind the nuts and the amount of time nuts were repeatedly ground in this spot. The appearance of these depressions indicates a long history of indigenous habitation in the surrounding area.

Bedrock mortars with Dr. Brooks’s dog Red

Dudley Park sign

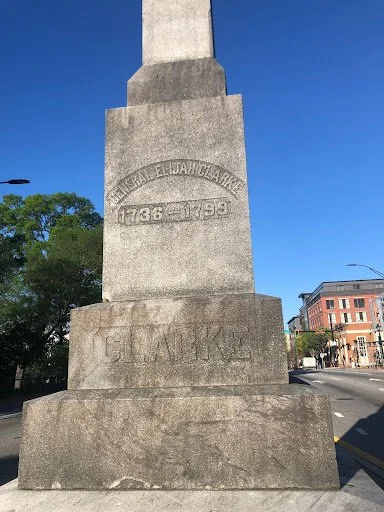

Elijah Clarke Monument

Across from the Arch, Broad Street, Athens, GA

Nearby Parking: On-street metered parking is available

Erected in 1904 by the Daughters of the American Revolution, this monument is dedicated to Elijah Clarke. Born in 1742, Clarke grew up in North Carolina and served as a militia captain in the Revolutionary War, fighting both the British and Native Muscogee and Cherokee tribes. During the war, his victory at the Battle of Kettle Creek was met with great celebration and Clarke was awarded a plantation for his efforts. After the war for Independence was won, Clarke was involved in many political spheres and became a member of the Georgia Assembly from 1781 to 1790. Clarke also served as Commissioner for Native Americans. Despite his political title, Clarke was a major advocate for indigenous removal and was regarded as an “Indian Killer.” After the Jack’s Creek battle against the Muscogee people in 1787 which resulted in the death of roughly 25 native people, Athenian settlers revered Clarke once again, considering him the hero of the battle and adding to his notoriety in the town. Due to his popularity, Clarke County was named for him in 1801.

-

In the 1780s, the federal government took over Indian affairs. With increased hostility between Georgians and Muscogee people after a series of treaty disagreements, George Washington invited Muscogee leader, Alexander McGillivray, to New York in 1787 to discuss cessions of Muscogee land in Georgia. Despite the unequal power dynamic of the meeting, McGillvray’s shrewd negotiation skills secured the Treaty of New York which restored a portion of Muscogee land to the tribe and established federal policy on Indian affairs.

To defend their land, the Muscogee people created a unit that would patrol the border of their territory in hopes of making settlers adhere to treaty obligations. The Georgian perspective recalls these border patrols as violent ambushes, but that was not the case. In Patrolling the Border, Joshua Haynes explains that most patrols were peaceful with few ending in violence. Despite the outcome of these patrols, Georgians viewed them with disdain, especially Elijah Clarke.

A decade after the Treaty of New York, frustrated with the federal government, Clarke crossed into the sovereign territory of the Muscogee people. In doing so he actively violated treaty rights, attacked the patrolling guards that had been on a lunch break, and claimed the land as his. With his forcefully acquired land, Clarke attempted to create his own government titled the Trans-Oconee Republic in 1794. His government was quickly dissolved by the Georgia militia, sent under pressure from George Washington. Clarke surrendered to the militia without a fight and returned to Georgia lands.

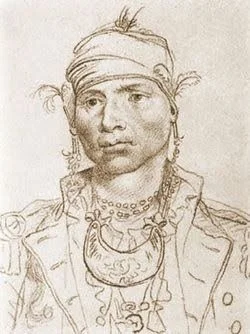

Elijah Clarke

Creek Headman Hoboithle Micco “The Tallasee King,” a delegate to the Treaty of New York negotiations in 1790

Elijah Clarke Monument

Elijah Clarke Monument, Front Inscription

Elijah Clarke Monument, Side Inscription

Acknowledgments

James Brooks

Michelle Nguyen

RaeLynn Butler

Miranda Panther

Caitlin Short

Amy Andrews

Steven and Beth Brown

Sources

RaeLynn Butler

Miranda Panther

Steven and Beth Brown

Mark Williams

James Brooks

Haynes, Joshua. Patrolling the Border: Theft and Violence on the Creek-Georgia Frontier 1770-1796. (Athens Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2018.)

McPherson, J. (2024, January 2). The Athens factory. Complex Cloth. https://complexcloth.org/the-athens-factory/

Scurry, Steven. “The Oconee War.” Flagpole. April 7, 2004. <https://flagpole.com/news/news-features/2004/04/07/the-oconee-war-3/

“A Brief History of Athens.” Visit Athens, GA. <https://www.visitathensga.com/plan/heritage/history-of-athens/

“Mississippian Culture.” National Park Services. Last updated July 26, 2023. <https://www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture/mississippian-culture.htm

“City of Athens: Early Athens History.” Athens-Clarke County Unified Government Website. <https://www.accgov.com/109/City-of-Athens#:~:text=Milledge%20purchased%20633%20acres%20from,and%20learning%20during%20ancient%20times.

Land Acknowledgement

The state of Georgia sits on the traditional and ancestral lands of the Muscogee, Seminole, and Cherokee Nations. After thousands of years of native inhabitance, indigenous displacement in Georgia began in 1732 with the establishment of the Georgia colony and continued until 1838. It is with respect that we acknowledge the painful history of displacement and forced removal as the Muscogee, Seminole, and Cherokee tribes were forcefully separated from their ancestral lands in Georgia.

It must be noted that land acknowledgments of this sort do not ease the pain of forced removal. This project aims to uncover and re-present the Indigenous history of Athens through research and consultation with the Muscogee and Cherokee tribes. We included their perspectives throughout this project to collaboratively tell their story. We plan on contacting three Seminole tribes, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and the Miccosukee Tribe of Florida, and will update the tour again after consulting with them.

Labor Acknowledgement

As a Southern state, Georgia’s history is entangled with the institution of slavery. In the Antebellum period, Georgia benefited from the economic prosperity of slaveholders and the manual labor of slavery. This legacy exists today as slave-made buildings populate the campus of the University of Georgia. This statement acknowledges those enslaved persons with respect and highlights how this painful history has been formative to our university, our city, our state, and our country.

Currently, at UGA, scholars have been working to bring these truths to light through projects like Slavery at UGA and Complex Cloth. Most recently, associate professor and School of Social Work Director of Global Engagement Jane McPherson has been working to uncover the history of the School of Social Work building through the Complex Cloth Project. According to her research, just two years after indigenous removal (1830), Georgians harnessed the waterpower of the shoals to create a textile mill titled the Athens Manufacturing Company, or the “Athens Factory.” At the Athens Factory, slave and child labor were used to transform slave-picked cotton into cloth. For more on the Complex Cloth project and the history of the School of Social Work, visit https://complexcloth.org/ .